Government Bonds: A Fiscal Solution or an Economic Risk?

Advertisements

Over the past 25 years, U.S. government debt has skyrocketed, rising at an alarming rate. This debt is now more than 120% of the country’s GDP. It's not just the United States facing such fiscal challenges; nations like the United Kingdom, the Eurozone, and even China are watching their government debts climb at a staggering pace. However, Japan stands out with a shocking debt-to-GDP ratio of 260%. This figure is sobering: it suggests that the average Japanese citizen would need to work for 2.6 years just to cover the government debt. Even if we consider Japan's 2022 government revenue, if the government decided to stop all spending, it would take a staggering 18 years to pay off its debt.

This brings up several pressing questions: Are these governments out of control? Why are they borrowing so much money? What underlies this pattern of borrowing? Might the U.S. even default on its debts? And why do some economists argue that borrowing might actually be beneficial? How do we determine what constitutes excessive borrowing? You may share these inquiries as we delve deeper into this complex economic landscape.

Every nation operates with a government structure that balances income and expenditure. Taking the U.S. as a case study over the past 30 years, approximately 95% of its government income comes from taxation, while expenditures cover infrastructure, public services, and national defense among other areas. Typically, government spending exceeds revenue, which economist-speak refers to as a persistent fiscal deficit. And when expenses exceed income, governments often resort to issuing bonds to finance the shortfall. This pattern of carrying a fiscal deficit is common in other economies as well, including China, Japan, the U.K., and across the Eurozone. In contrast, if a household managed its finances in such a manner, it would likely earn the label of 'irresponsible'; yet this fiscal behavior is viewed differently on a national scale.

Consider the contentious issue of the debt ceiling in the United States. This is essentially a "symbolic" limit on the amount of money the government can borrow, set by congressional vote. At first glance, it appears a rational constraint, implying some level of self-discipline. However, this limit has been raised 42 times since 1981, averaging one adjustment per year. The truth is, if U.S. debt were to become problematic—say, if default occurred—the repercussions for the economy would be catastrophic. Predictions indicate that a debt default lasting a few weeks could lead to a 45% drop in stock market values, displacing over 8 million jobs. Consequently, the debt ceiling often serves as a battleground for political parties rather than a genuine fiscal constraint.

In the last two years, the government made a massive $5 trillion investment to stimulate the economy without negotiating over the debt ceiling. Now that the debt is nearing its limit, discussions are surfacing. Countries with debt ceilings are few, with Denmark being another. However, Denmark's limit is set at nearly three times its existing debts, rendering it nearly irrelevant.

Globally, government debt has climbed over the past half-century. Modern economists examine this trend through lenses shaped by significant historical insights. Adam Smith, the father of modern economics, introduced the theory of the "invisible hand," which contended that government intervention is generally against efficient market processes. In the 18th and 19th centuries, the U.S. largely adhered to his views, promoting competition and limiting governmental interference. Yet, unregulated market environments revealed their vulnerabilities; recurring economic meltdowns led notably to the Great Depression of 1929, during which the government’s reluctance to intervene was deemed a critical factor in the protracted economic downturn.

Against this backdrop, John Maynard Keynes proposed a reevaluation of previous theories, gaining traction as governments around the world began to embrace his ideas. In essence, his advocacy suggested that markets can fail and that government intervention is crucial—particularly during economic downturns. The government should borrow to stimulate demand and prevent crises.

Despite criticisms of Keynesian economics, many of his core ideas endure in modern policy approaches. When economies face downturns, governments tend to adopt expansive fiscal policies by inheriting debt to foster recovery. The 2008 subprime mortgage crisis in the U.S., the COVID-19 pandemic, Japan's multiple financial crises in the late 1990s and beyond, as well as the European debt crisis, are notable examples. Still, it is crucial to acknowledge that money spent does not always yield the desired effect; Japan's extensive borrowing over the past 30 years did not translate into corresponding economic growth.

The preceding discussion of government spending is grounded in established economic theory. Recently, a revolutionary notion known as Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) has gained traction. This theory posits that governments should borrow confidently, as increased government spending stimulates benefits for the non-government sector. Government credit equates to money, and so long as there is no rampant inflation, borrowing aggressively could be advantageous. Though this theory has not yet penetrated mainstream economic thought, its popularity continues to rise.

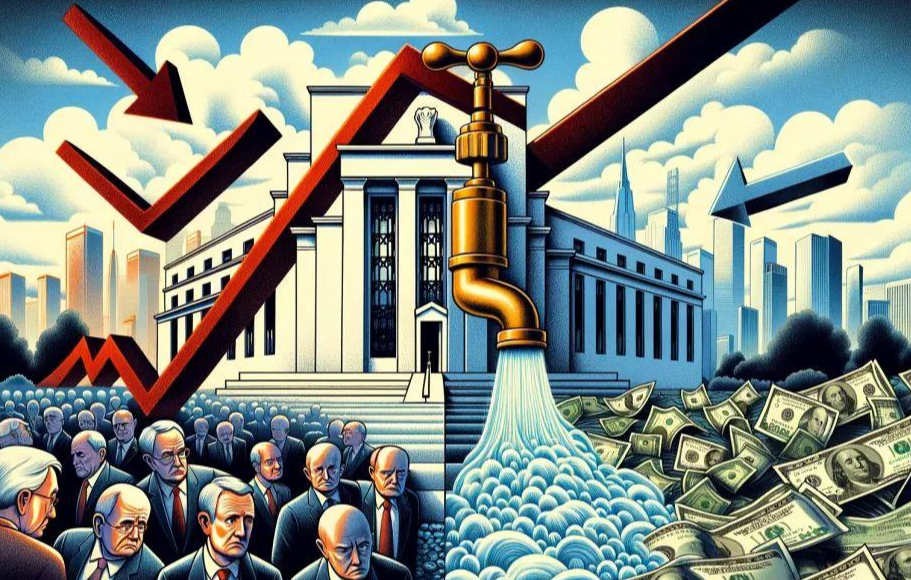

While government borrowing can potentially stimulate employment and enhance the economy, it is not without limitations. A crucial difference lies in the government's unique power to print money. Some may argue that only central banks can create money, not governments themselves. Indeed, modern structures often separate government from central bank functions. However, mechanisms exist whereby central banks can effectively finance government expenditures through purchasing government securities, an approach classified as quantitative easing. This process involves intermediaries but results in a direct loan flow to governments.

When it comes to national debt, domestic debt, or bonds issued in a country’s own currency, presents different implications. During the gold standard era, such debts were limited, curbing excessive printing. However, under modern fiscal frameworks, governments can print more money to avert domestic defaults relatively easily. Contrarily, external debt denominated in foreign currencies—such as U.S. dollars—places countries, excluding the U.S., in precarious positions. These governments cannot print dollars; instead, they must solicit foreign debt, leading potentially to defaults.

If domestic debt serves as a buffer against economic fluctuations, external debt acts as a magnifier of economic activity. This dichotomy stems from the inherent characteristics of debt as a leverage mechanism. During robust economic periods, capital floods into investments, allowing nations to ramp up external borrowing to seize opportunities. However, when crises arise, capital can swiftly flee, exacerbating the economic decline. Historical precedents establish a strong linkage between national economic collapse and debt crises, often ignited by external debt defaults—for instance, the Latin American crisis of the 1980s saw nations like Argentina and Mexico spiraling down due to unmanageable external commitments.

Looking to the European debt crisis, we can observe a potential paradox within the Eurozone. While countries banded together using a common currency and central banking system, individual states retained control over fiscal policies, effectively converting domestic debt into foreign debt. As a result, nations such as Greece, Italy, and Spain faced severe issues, with increasing risk of defaulting on their debts. The European Central Bank refrained from purchasing these nations' bonds to maintain credibility, leading to reliance on external financial support and giving rise to austerity measures mandated by the International Monetary Fund (IMF)—further aggravating the economic malaise within these countries.

Economic crises, such as the 1997 Asian financial crisis, the 1998 Russian and Ukrainian defaults, the 2001 Argentine crisis, and the recent turmoil in Sri Lanka, have all been attributed to the inability to service external debt obligations. This suggests a sentiment—that "domestic debt isn't really debt" is overly simplistic. Of course, domestic debt is indeed debt; however, the controllability factor is higher, allowing governments to manage domestic obligations with greater latitude, particularly in times of emergency.

Focusing on serious debt crises, two fundamental antecedents can often emerge. The first is interest rates—central to financial markets, the prices of government bonds dictate the landscape of risk-free rates. Bond issuance can inflate supply, leading to a decline in prices, which in turn elevates overall interest rates. This dynamic impacts not just government bonds but corporate bond rates, as highly rated corporate bonds are priced relative to government benchmarks, ultimately hindering consumption, investment, and economic activity.

When a government’s tax revenue falls short of meeting interest obligations, a vicious cycle ensues. In extreme cases, if the average interest rate on Japanese debt were to rise to 5%, the government would struggle to cover even interest payments with its overall revenues. However, Japan hasn’t reached that point; historical data indicates that even as the nation has amassed significant debt, only 11% of its revenue is currently used in servicing interest.

One method by which Japan has mitigated the risks associated with rising interest rates involves the Bank of Japan's aggressive monetary policy since 2013. Amidst substantial debt accrual, the government was particularly concerned with potential interest rate increases due to bond markets. Consequently, the central bank engaged in extensive purchases of government bonds, driving prices up and effectively compressing interest rates.

By 2020, Japan adopted an even bolder strategy, setting a goal to keep interest rates on 10-year government bonds below 0.25%, adjusting this target to 0.5% in recent years. The sheer volume of government bonds held by the Bank of Japan is a testament to the central bank's commitment to abate interest rate spikes; thus, while the government continues to borrow heavily, the burden of servicing debt remains unexpectedly light.

Whenever concerns arise regarding the U.S. Treasury's debt levels, officials often assert that despite high borrowing, low interest rates provide favorable conditions for economic stimulus. The implication suggests that with manageable borrowing costs, the government can simultaneously foster growth while minimizing risk, demonstrating the delicate balance that policymakers strive to achieve when contemplating fiscal maneuvers.

Nevertheless, the financial reality is that there are no free lunches, and inflation remains a perennial concern. When inflation surges, it can handicap governments’ abilities to sustain borrowing practices. While increased expenditures can alleviate weak demand or job shortages, inflation presents a formidable adversary. In instances where inflation dominates, central banks often abandon their earnings-sensitive policies, reverting to more restrictive measures to deter price rises, recalling historical lessons that underscore the hardships presented by combating inflation.

You may wonder then, if the U.S. faces significant inflation challenges, why must it raise its debt ceiling? The stark reality is that funds have already been allocated; thus, the government must reconcile expenditures that were made in the past. Had U.S. policymakers anticipated that the stimulus packages in 2021 would trigger elevated inflation and provoke aggressive rate hikes by the Federal Reserve, they might have approached funding with greater caution.

Once these two constraints have been identified, gauging an appropriate debt level becomes feasible. As long as a country remains within these defined limits; its debt issuance becomes a matter of balancing economic growth with maintained stability. Diverse nations adopt unique strategies; for instance, Denmark manages its debt below 50% of GDP, while Sweden, Norway, and Holland typically prioritize gradual growth over aggressive expansion policies. In contrast, the pursuit of rapid growth defines the practices of the U.S. and Japan, while China navigates a distinct landscape marked by varying local debt challenges.

In conclusion, every country must find a middle ground in terms of debt issuance, ensuring that interest rates do not inhibit economic growth while also preventing defaults and uncontrolled inflation. This measure is not a fixed figure; rather, it relies on the overarching economic environment. When interest rates and inflation remain low, public trust in government operations potentially allows governments to handle seemingly high debt levels without disastrous consequences, just like in pre-pandemic America, Europe, and Japan.

However, circumstances today differ markedly, with the yield on the 10-year U.S. Treasury bond having escalated from 0.6% to approximately 3.7% over the past three years, and inflation swelling from negligible levels to about 4.9%. Similar trends are echoed in Japan and Europe, revealing that a debt ratio of 260% previously appeared manageable, yet now does not bode well.

Should a nation find itself in a predicament of excessive debt amid rising inflation, the solutions available are limited. Generally, three main paths exist.

The first route is fiscal austerity, a direct response to excessive borrowing—cut back on spending and borrowing. The U.S. has experienced government shutdowns due to budget impasses, exemplifying such tension. While sometimes temporary closures last only a few days, longer standoffs—in 2019, for example—halted government functions for 35 days, obstructing paychecks for over 800,000 federal employees. However, these measures rarely address the foundational issues; imposing drastic austerity can severely injure economic growth, frequently resulting in resistance. Such drastic actions are typically reserved for situations where nations are cornered.

An alternative, and perhaps more drastic, approach is to default or restructure debt. Many may not realize that government defaults differ significantly from corporate bankruptcies. A company's default could lead to liquidation and asset sales; however, government default poses limited risks to the owners of government securities. Historical instances wherein military action was used to collect debts are now rare, and current default ramifications mainly revolve around diminished credibility and future financing difficulties.

In modern economies, reliance on credit systems is crucial, especially in developed nations. This reliance makes the repercussions of a sovereign default monumental, with spiraling shifts in market confidence leading to currency depreciation. Re-establishing credibility can take years. The U.S. government has warned that missing even a few interest payments would potentially lead to millions of job losses. Even so, it must be acknowledged that internal defaults can still manifest, evidenced by 84 instances occurring globally from 1980 to 2022, typically correlating with failures in external debt repayment.

Finally, most governments prefer to leak out of crises rather than confront them directly; they either roll over debts through new borrowings or resort to money printing—or a combination of both strategies. Within a context of stagnant economies and inflation, investing in burgeoning sectors might have surprising outcomes. For example, an investment in electric vehicle technology could trigger unanticipated advances, aiding economic recovery and mitigating inflation pressures.

While such a scenario is unlikely, the propensity of governments to prolong debt issues using borrowing or printing often leads to a deeper rut. The hesitance to face these dilemmas directly is partially a function of political structures, where public sentiment surrounding austerity or defaults weighs heavily on policymakers' decisions. Given that policies aimed at delay are expansionary and generally yield lower short-term social impact, they often receive public endorsement.

Leave a Comments